Sometimes research reports are really full of jargon and hard to read. But I've found some tricks that help me understand them better. (Evaluating them will be in a separate blog post.)

I spend a lot of time on Pubmed.gov, because most research is available there. (Google Scholar includes little of the research, so I avoid it.) What's available here are abstracts (summaries) of research, and sometimes links to the full articles.

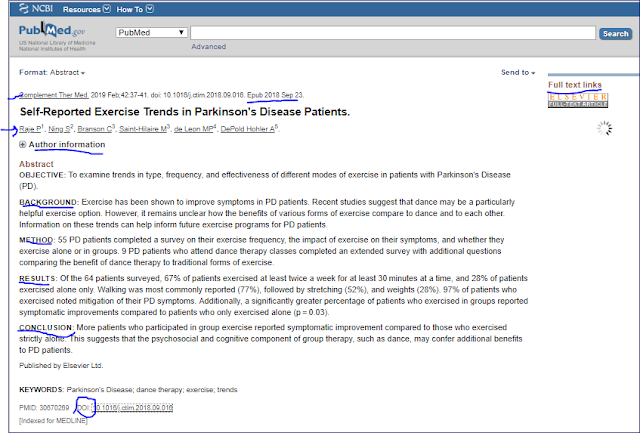

Here's an example of a recent abstract that has been marked to help you identify useful information:

Here are a few things that I do:

Read the Conclusion first (not all abstracts contain these helpful headers, but at least the conclusion will be at the end). This tells us that: "More patients who participated in group exercise reported symptomatic improvement compared to those who exercised strictly alone..." Hm, so pwp are doing better in group exercise.

If I want to know more, I move up to Results. This tells me some statistics (which I understand some of the time), and more details than the Conclusion. For instance, 97% of those who exercised improved their symptoms.

How was the study done? How many were involved? For this, I move up to Method / Methods. This tells me and number of patients or healthy people were studied, and what action was taken; in this case, it was a survey.

Background will tell briefly about the reasoning or earlier research that lead to this study.

Up at the top are the title and the authors; if I want to know more about who did the research, I can click on + Author Information (in Pubmed, not in the illustration). At the top is also the journal name and the publication date; often there is an Epub date, date published online, that may be earlier than the "official" publication date. This tells me how recently the work was done.

Often this is enough, but sometimes I want to know more. For instance, how old were the subjects, or what mix of genders. Maybe I want to know more about the methodology that was used. In that case, I need to read the full paper; sometimes I can reach it, either by clicking on Full Text Links (upper right) or on the DOI number (lower left). Since I've had better luck with the DOI number (Digital Object Identifier), if the Full Text Link doesn't say "Free," I click on DOI. Sometimes all that I can find there is the abstract, but sometimes, with some publishers, there is more. Some publishers include Highlights, the essential findings, which can be more useful than the abstract for telling about key findings:

Sometimes I can see the full paper, as in this case; the abstract is at the beginning of the paper, and then the full paper follows.

If I want more, the Discussion section of the full paper often has some of the most interesting material; it's here that researchers often compare their findings to those of different researchers, or reflect on what their results mean.

Sometimes the full paper is behind a Paywall; that means I need to be a subscriber to the journal or a medical/scientific database of these articles, or be willing to pay around $35 to read the paper - which I'm not. If you think you'll routinely want to read whole papers, cultivate a friend or family member who has access to these articles for their work, perhaps somebody in the scientific or medical field.

I'll be explaining how to evaluate a paper in a future blog post. For now, post a comment if you have a question, so that I can reply.

Monday, May 27, 2019

Monday, May 20, 2019

The legal side of PD

I like to live in the now, avoiding fretting about the future and idealizing the past. But I do need to make plans.

What medical care do I want (or not want) if I'm terminal, seriously ill, or in a coma? (Here's where you want a Living Will/Advanced Directive - I found Five Wishes to be particularly good for helping me think through what I would like, and it's legal throughout the US.)

What if I become unable to direct my medical care? My mom, who had PD, developed dementia. That's just one of many scenarios. (Here's where you need to name a Health Care Representative. In some states, that's part of the Living Will.)

What if I can't direct my financial affairs? (Here's where you need a Power of Attorney, to give somebody that you've chosen the authority to manage your financial affairs.)

How can I make handing over my assets easier on my family? Having a will means that I can control where my money goes. Avoiding probate is primarily for avoiding all the time it takes. Wouldn't it be great that my family could put the house on the market immediately, for example, and not have to wait a year? (Here's where you need a Will, and maybe a Living Trust)

What about brain or other organ donation? (You can arrange for brain donation - for research - in advance, and can often include other organ donations on your driver's license)

What kind of memorial service/funeral do you want? If you want your ashes scattered, where? (Five Wishes addresses this, and you can also arrange for and pay for everything in advance.)

What are your userids and passwords so that 1) someone can take over your financial affairs when necessary, and 2) so somebody can close your social media accounts if you can't be on them any more? (This means maintaining a list, and letting key people know where it is.)

Recently, my husband and I sat down with a competent estate-planning/elder law attorney to talk about what we needed. It cost us a chunk of change, but 1) now my affairs are set up the way I want them to be, and 2) it is a huge relief. Our wishes have been made clear. Our kids have a knowledgeable firm to go to for help if they need it. In addition, our assets are available to us now, but can easily pass to our kids when we are both gone.

This is not trivial. My condition means that I can fall and hit my head, develop dementia, have delusions, or become unable to communicate my wishes. I want my wishes to be respected, so I need to 1) decide what they are, and 2) identify who can respect them, and 3) give them the authority to act.

I recommend this book, Estate Planning for People with a Chronic Condition or Disability. But this isn't enough: surfing the web for "free" tools, especially when the law varies from state to state, is not the ideal approach. Finding the right attorney is much better, in my opinion; start asking around.

Images from Pixaby, Five Wishes, Amazon.

What medical care do I want (or not want) if I'm terminal, seriously ill, or in a coma? (Here's where you want a Living Will/Advanced Directive - I found Five Wishes to be particularly good for helping me think through what I would like, and it's legal throughout the US.)

What if I become unable to direct my medical care? My mom, who had PD, developed dementia. That's just one of many scenarios. (Here's where you need to name a Health Care Representative. In some states, that's part of the Living Will.)

What if I can't direct my financial affairs? (Here's where you need a Power of Attorney, to give somebody that you've chosen the authority to manage your financial affairs.)

How can I make handing over my assets easier on my family? Having a will means that I can control where my money goes. Avoiding probate is primarily for avoiding all the time it takes. Wouldn't it be great that my family could put the house on the market immediately, for example, and not have to wait a year? (Here's where you need a Will, and maybe a Living Trust)

What about brain or other organ donation? (You can arrange for brain donation - for research - in advance, and can often include other organ donations on your driver's license)

What kind of memorial service/funeral do you want? If you want your ashes scattered, where? (Five Wishes addresses this, and you can also arrange for and pay for everything in advance.)

What are your userids and passwords so that 1) someone can take over your financial affairs when necessary, and 2) so somebody can close your social media accounts if you can't be on them any more? (This means maintaining a list, and letting key people know where it is.)

Recently, my husband and I sat down with a competent estate-planning/elder law attorney to talk about what we needed. It cost us a chunk of change, but 1) now my affairs are set up the way I want them to be, and 2) it is a huge relief. Our wishes have been made clear. Our kids have a knowledgeable firm to go to for help if they need it. In addition, our assets are available to us now, but can easily pass to our kids when we are both gone.

This is not trivial. My condition means that I can fall and hit my head, develop dementia, have delusions, or become unable to communicate my wishes. I want my wishes to be respected, so I need to 1) decide what they are, and 2) identify who can respect them, and 3) give them the authority to act.

I recommend this book, Estate Planning for People with a Chronic Condition or Disability. But this isn't enough: surfing the web for "free" tools, especially when the law varies from state to state, is not the ideal approach. Finding the right attorney is much better, in my opinion; start asking around.

Images from Pixaby, Five Wishes, Amazon.

Monday, May 13, 2019

Donating your brain for research

Since there's a narrow window after you die to donate your brain, this is something you (or your family) will ideally do in advance. Um. Why would you want to?

Well, to assist research into PD and related conditions. And so your family (and your doctor) will know what your actual diagnosis is (nobody knows for sure until they look at your brain microscopically, and that can't be done while you're alive). I won't be able to benefit from this, but others with PD will, and my family is likely to benefit as well.

Here is a great Ted Talk that explains more:

The Brain Donor Project was set up to encourage brain donation in association with the US National Institute of Health's https://neurobiobank.nih.gov/. If you asked the NeuroBiobank about brain donation, they will refer you to the Brain Donor Project (which is run by volunteers, so please be patient).

So here's how you do it. https://braindonorproject.org/ I filled out the contact form and they referred me to the Brain Bank at Harvard, which is just a few hours away from where I live. This is important because the brain needs to be donated and preserved within less than 24 hours of death; each individual bank has their own requirements and some have a much smaller window of time when they will accept donation.

I went on the Brain Bank's website, found their form, indicated my diagnosis on the form, along with my intent to donate my brain. Looking at their website, they commit to determining correct diagnosis (which I want for my family), and preserve the brain so that it can be used by hundreds of researchers. This form just indicates my intent (and gave me their 24 hour phone number.) Each brain bank will be a bit different. When my disease gets more advanced, I (or my Health Care Representative) will contact them to make more specific arrangements.

This gets a bit grizzly, now, so skip this paragraph if you're squeamish. Ideally, when you are close to death, your family/hospice workers/etc. notifies the brain bank. When you actually die, the brain bank needs to be notified immediately (that's why the 24 hour phone) so they can swing into action: notify the neuropathologist who will collect the brain at the hospital or funeral home, notify the hospital/funeral home of need to remove brain, have the neuropathologist collect the brain and send it pronto to the brain bank, where the brain bank preserves the brain and begins work on diagnosis. Clearly, there are legal forms needed, which is why doing this ahead of time - if possible - is so important.

Here are some Frequently Asked Questions: https://braindonorproject.org/faq/ For instance, yes, you can still have an open casket if you'd like one. No, your driver's license organ donor form is not enough (that's for a different kind of organ donation.) No, this does not substitute for a funeral/memorial service/cremation/burial for a loved one.

This is part of my preparing-for-the-future. Long-term, I hope to be part of the solution.

Well, to assist research into PD and related conditions. And so your family (and your doctor) will know what your actual diagnosis is (nobody knows for sure until they look at your brain microscopically, and that can't be done while you're alive). I won't be able to benefit from this, but others with PD will, and my family is likely to benefit as well.

The Brain Donor Project was set up to encourage brain donation in association with the US National Institute of Health's https://neurobiobank.nih.gov/. If you asked the NeuroBiobank about brain donation, they will refer you to the Brain Donor Project (which is run by volunteers, so please be patient).

So here's how you do it. https://braindonorproject.org/ I filled out the contact form and they referred me to the Brain Bank at Harvard, which is just a few hours away from where I live. This is important because the brain needs to be donated and preserved within less than 24 hours of death; each individual bank has their own requirements and some have a much smaller window of time when they will accept donation.

I went on the Brain Bank's website, found their form, indicated my diagnosis on the form, along with my intent to donate my brain. Looking at their website, they commit to determining correct diagnosis (which I want for my family), and preserve the brain so that it can be used by hundreds of researchers. This form just indicates my intent (and gave me their 24 hour phone number.) Each brain bank will be a bit different. When my disease gets more advanced, I (or my Health Care Representative) will contact them to make more specific arrangements.

This gets a bit grizzly, now, so skip this paragraph if you're squeamish. Ideally, when you are close to death, your family/hospice workers/etc. notifies the brain bank. When you actually die, the brain bank needs to be notified immediately (that's why the 24 hour phone) so they can swing into action: notify the neuropathologist who will collect the brain at the hospital or funeral home, notify the hospital/funeral home of need to remove brain, have the neuropathologist collect the brain and send it pronto to the brain bank, where the brain bank preserves the brain and begins work on diagnosis. Clearly, there are legal forms needed, which is why doing this ahead of time - if possible - is so important.

Here are some Frequently Asked Questions: https://braindonorproject.org/faq/ For instance, yes, you can still have an open casket if you'd like one. No, your driver's license organ donor form is not enough (that's for a different kind of organ donation.) No, this does not substitute for a funeral/memorial service/cremation/burial for a loved one.

This is part of my preparing-for-the-future. Long-term, I hope to be part of the solution.

Monday, May 6, 2019

Questions to ask about a Clinical Trial

I came across this presentation recently about questions you should ask before participating in a clinical trial. They're great questions, so I wanted to share them. I had some of these questions, others, too, and there were still others I had not thought of. You probably have other questions, too.

Remember that a clinical trial involves risk - at the very least, the proposed treatment might not work. But it could also cause harm, and even, though rarely, death. So ask!

First, some things to think about up front:

Just came across this, written by Simon Stott (The Science of Parkinsons blog) about some rules to follow once you're in a clinical trial.

Image from Pixabay.

Remember that a clinical trial involves risk - at the very least, the proposed treatment might not work. But it could also cause harm, and even, though rarely, death. So ask!

First, some things to think about up front:

- How will this fit into my schedule?

- What am I planning or hoping to get out of participating? (Find a better treatment for me, help all pwp, etc.)

- What matters to me the most about participating in this trial?

- What does my own doctor think about how this might fit into my care plan/safety/etc?

- What is the study trying to accomplish?

- Who, exactly, is conducting this research? (For example, is it being done for a drug company?)

- What have these researchers (and others) found out about this treatment?

- Have the results of previous research been published? (If not, why not?)

- What risks are there, and what are the possible benefits?

- Is there a placebo? (The equivalent of a sugar pill, a placebo helps determine what reaction is due to "placebo effect" - hopefulness that this will work vs. how well it really works.) If I receive a placebo, will I have the opportunity to receive the real treatment later on? How does a placebo work in the case of a surgical study?

- How long will the study go, and how often will I be needed?

- What form will the treatment take? (pill, shot, surgery, specific exercise...)

- What other tests are involved? Do these tests involve risk? Pain? Who will conduct these tests? (For example, if a spinal tap is being done, what are the risks from this test, and how much training/experience does the person have who will conduct the test?)

- How will my privacy (health, personal information, test results, etc.) be protected?

- What will happen at each visit?

- If I decide to leave the study early, what needs to happen? (for example: slow reduction of drug, surgical removal of hardware)

- What happens if my condition gets worse, or I am injured/made sick because of the trial? Who will pay for my care?

- What if I have an adverse reaction when I'm away on vacation? Who should I see for care? If I need an emergency room visit, will I be reimbursed for the cost?

- Will any travel costs be paid for, and if so are there limits on distance?

- How about taxis or meals?

- Is the location where the study takes place in my insurance network? If not, will the study pay costs for tests that insurance would usually cover?

- If there are any lab tests that help the study but are not "medically necessary" who will pay for these tests?

- Is there a copay cost to see a specialist/specialists that I will need to pay?

- If my insurance is needed to pay for some costs, who will submit the costs to insurance?

- What happens after the study?

- Is there follow-up care needed? Who will provide that, and who will pay for this care?

- Will I have access to test results, and to whether I received placebo or active therapy? When will this information be available?

- Is there a way for me to continue to take the drug/use the device after the trial is over, if it helps me? Who will I need to speak to?

Just came across this, written by Simon Stott (The Science of Parkinsons blog) about some rules to follow once you're in a clinical trial.

Image from Pixabay.

Friday, May 3, 2019

What I wish I had known... being first diagnosed with PD

It was December 20, 2016. It was like a bomb went off close by, so I couldn't hear anything for awhile. My neurologist had made sure it wasn't MS/stroke/Lyme/vitamin deficiency and a host of other things that look like Parkinson's, but aren't. I was pretty sure he was going to say I had PD - after all, my mom and her brother both had it, and I knew something was very wrong.

But hearing the diagnosis confirmed... I didn't hear anything for awhile. Fortunately, my husband and daughter were both there to listen.

I read a lot then, but not everything soaked in, because in the background my mind was shouting, OMG OMG OMG OMG OMG...

What I wish I had known immediately, because it would have helped me focus on living (and might have helped my family, too):

Exercise is critical - not only will it help you feel better, but if vigorous enough, it seems to slow progression and improve symptoms. Fortunately, I already had an exercise habit at dx (diagnosis). For more.

Find other pwp. They provide support, they understand, and they have resources. Support group, online forums, PD exercise group - all places to find your new peers. Set aside your assumptions about age, or gender. You have a lot in common.

Watch out for snake oil as well as for the over-enthusiastic press. There are people who want to make a buck out of your worry. See here and here and here and here and here. And the press will report that there is a cure - but it turns out the hopeful results were in ... mice. It's important to find valid sources for information - talk show hosts, internet advertisements, and your brother-in-law's cousin's buddy are not it. I heartily recommend The Science of Parkinson's.

Alternative / complementary medicine has not been found to cure PD, but it can help make you more comfortable. So. Why. Not?

Find a movement disorder specialist - a neurologist who has extra training and experience with PD. You may see your primary care doctor or your neurologist more often, but a MDS can make a huge difference in diagnosis and care. And be sure you can phone/email/patient portal when you have questions or concerns; getting your medications/dosage right or dealing with an alarming new symptom are not matters to wait for the next appointment in weeks or months. In the US, you can use https://parkinson.org/Living-with-Parkinsons/in-your-area. Or email your location to info@movementdisorders.org.

Be proactive. I am not sorry that I found a good physical therapist who is experienced with PD. Or that I found a good speech therapist. And saw them when my problems were minor. Specialists like these can really help you now - don't wait until you can't get out of a chair, or you can't swallow or your voice is so quiet that nobody can hear you. They can give you exercises that will help you stay on top of symptoms before they get overwhelming. (I remember to do all those exercises by pairing them with an activity - like feeding the dog, or being in the car - that reminds me to do them.)

Read Every Victory Counts, published by the Davis Phinney Foundation. This includes the voices of pwp and their families, addresses complementary therapies, as well as more mainstream therapies. It is focused on living your best life now, and is much more helpful than many of the conventional books written by physicians. Available for free download and sometimes also in paper - free.

Recognize that this may be as hard for your family to grasp as it has been for you. Some will be in denial, telling you that It's all in your head. Sometimes because they don't deal with illness well. Sometimes because this shifts your roles - maybe you were the caregiver and that can't be any more. Some will have opinions about your choices for treatment, forgetting that these are your choices. While they are adjusting, being with other pwp is very helpful. Take family to a support group, too.

Live in the present, but plan for the future. Grab bars in the bathroom. Living will and other legal papers. Investigate the care you might need down the road. My mom needed, eventually, 24 hour care, because she could not stand or walk; not everybody reaches that point, but you may have to deal with it. And don't assume that your spouse can do everything - because even a few hours of physical care can be exhausting to provide.

If you're inclined to participate in finding better therapies, then explore being part of a clinical trial - a scientific study to find out more about possible PD treatments.

Focus on what you CAN do. At the start, PD will remind you of what's hard to do, and you will have this loud volume reminder (OMG I have PD), but if you are wise, in time you just move on to what IS. This is not passive resignation, it is facing reality but living your best life anyway. Michael J. Fox provides a great example of this (but so do many, many others).

This one is hard: accept help. And even harder: ask for help. Getting my cane was a revelation; so many strangers held doors for me. I don't always need it, but that handicapped parking sticker is a Godsend when I do. Exhaustion does not make PD better. People really do like to help.

But hearing the diagnosis confirmed... I didn't hear anything for awhile. Fortunately, my husband and daughter were both there to listen.

I read a lot then, but not everything soaked in, because in the background my mind was shouting, OMG OMG OMG OMG OMG...

What I wish I had known immediately, because it would have helped me focus on living (and might have helped my family, too):

Exercise is critical - not only will it help you feel better, but if vigorous enough, it seems to slow progression and improve symptoms. Fortunately, I already had an exercise habit at dx (diagnosis). For more.

Find other pwp. They provide support, they understand, and they have resources. Support group, online forums, PD exercise group - all places to find your new peers. Set aside your assumptions about age, or gender. You have a lot in common.

Watch out for snake oil as well as for the over-enthusiastic press. There are people who want to make a buck out of your worry. See here and here and here and here and here. And the press will report that there is a cure - but it turns out the hopeful results were in ... mice. It's important to find valid sources for information - talk show hosts, internet advertisements, and your brother-in-law's cousin's buddy are not it. I heartily recommend The Science of Parkinson's.

Alternative / complementary medicine has not been found to cure PD, but it can help make you more comfortable. So. Why. Not?

Find a movement disorder specialist - a neurologist who has extra training and experience with PD. You may see your primary care doctor or your neurologist more often, but a MDS can make a huge difference in diagnosis and care. And be sure you can phone/email/patient portal when you have questions or concerns; getting your medications/dosage right or dealing with an alarming new symptom are not matters to wait for the next appointment in weeks or months. In the US, you can use https://parkinson.org/Living-with-Parkinsons/in-your-area. Or email your location to info@movementdisorders.org.

Be proactive. I am not sorry that I found a good physical therapist who is experienced with PD. Or that I found a good speech therapist. And saw them when my problems were minor. Specialists like these can really help you now - don't wait until you can't get out of a chair, or you can't swallow or your voice is so quiet that nobody can hear you. They can give you exercises that will help you stay on top of symptoms before they get overwhelming. (I remember to do all those exercises by pairing them with an activity - like feeding the dog, or being in the car - that reminds me to do them.)

Read Every Victory Counts, published by the Davis Phinney Foundation. This includes the voices of pwp and their families, addresses complementary therapies, as well as more mainstream therapies. It is focused on living your best life now, and is much more helpful than many of the conventional books written by physicians. Available for free download and sometimes also in paper - free.

Recognize that this may be as hard for your family to grasp as it has been for you. Some will be in denial, telling you that It's all in your head. Sometimes because they don't deal with illness well. Sometimes because this shifts your roles - maybe you were the caregiver and that can't be any more. Some will have opinions about your choices for treatment, forgetting that these are your choices. While they are adjusting, being with other pwp is very helpful. Take family to a support group, too.

Live in the present, but plan for the future. Grab bars in the bathroom. Living will and other legal papers. Investigate the care you might need down the road. My mom needed, eventually, 24 hour care, because she could not stand or walk; not everybody reaches that point, but you may have to deal with it. And don't assume that your spouse can do everything - because even a few hours of physical care can be exhausting to provide.

If you're inclined to participate in finding better therapies, then explore being part of a clinical trial - a scientific study to find out more about possible PD treatments.

Focus on what you CAN do. At the start, PD will remind you of what's hard to do, and you will have this loud volume reminder (OMG I have PD), but if you are wise, in time you just move on to what IS. This is not passive resignation, it is facing reality but living your best life anyway. Michael J. Fox provides a great example of this (but so do many, many others).

This one is hard: accept help. And even harder: ask for help. Getting my cane was a revelation; so many strangers held doors for me. I don't always need it, but that handicapped parking sticker is a Godsend when I do. Exhaustion does not make PD better. People really do like to help.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Great tools to use during the Pandemic

Some organizations have stepped up for pwp who have lost socialization, and usually exercise programs and support groups. Even for those ex...

-

Looked into Marty Hinz and his amino acid supplementation, as I look into just about anything that might make PD easier. I have to say ...

-

There are members of the PD community who are convinced that following a ketogenic diet will slow progression. I had my doubts, but figured...

-

On his videos, Lonnie Herman swears that he's got the cure for Parkinson's, cancer, interstitial cystitis, you name it. He uses...